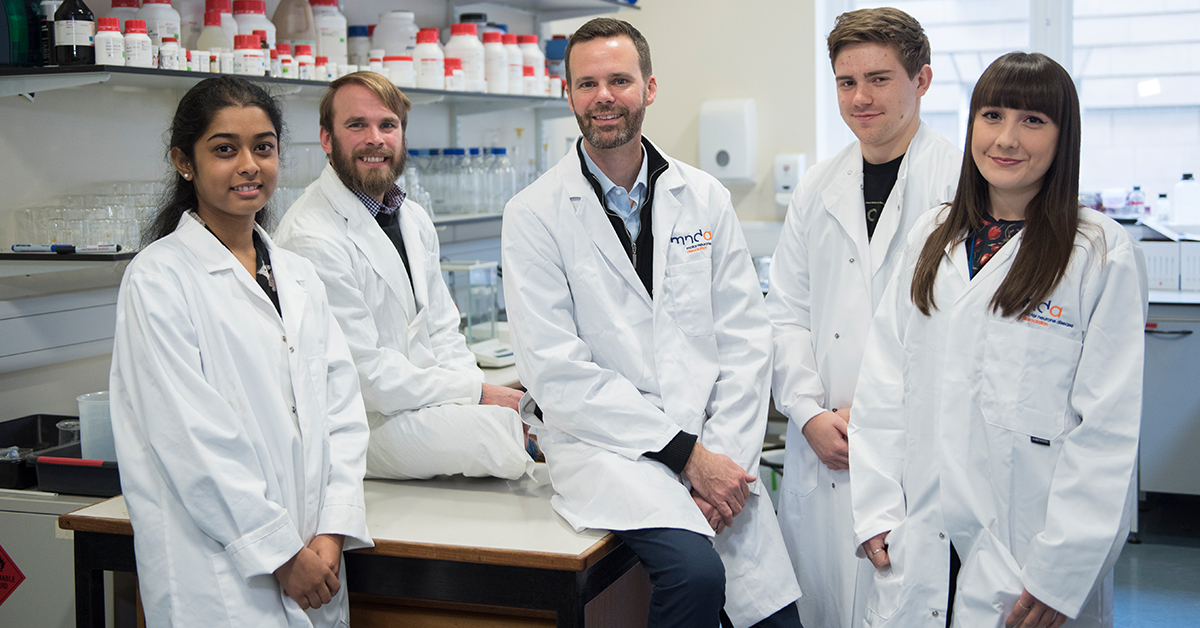

Based at the University of St Andrews since 2007, New Zealand born Professor Gareth Miles’ research is focused on motor control – the spinal circuits and neurons that control movement. His lab’s research was disrupted by the coronavirus crisis, but he found ways to make sure it didn’t bring his progress to a halt.

Going into cold storage

Lockdown was a fairly sudden thing for us. Of course, we’d been preparing for it, but in the end, we had to decide quickly to leave the lab – and that meant acting fast to make sure any projects involving tissues or cells were at a stage where they could be preserved.

We suggested to the University that we conduct simplified versions of as many experiments as possible, to get tissues ready for cold storage. Thankfully, they agreed – and for the first few months, the samples were maintained by the University’s team of essential workers.

It was a challenging time in many ways, but we still found ways of keeping up momentum.

A frustrating wait

Just before we went into lockdown, we’d managed to get some papers accepted for publication for a project that the MND Association is funding. One of those papers is a detailed analysis of the synapses – the connections between neurons in the spinal cord.

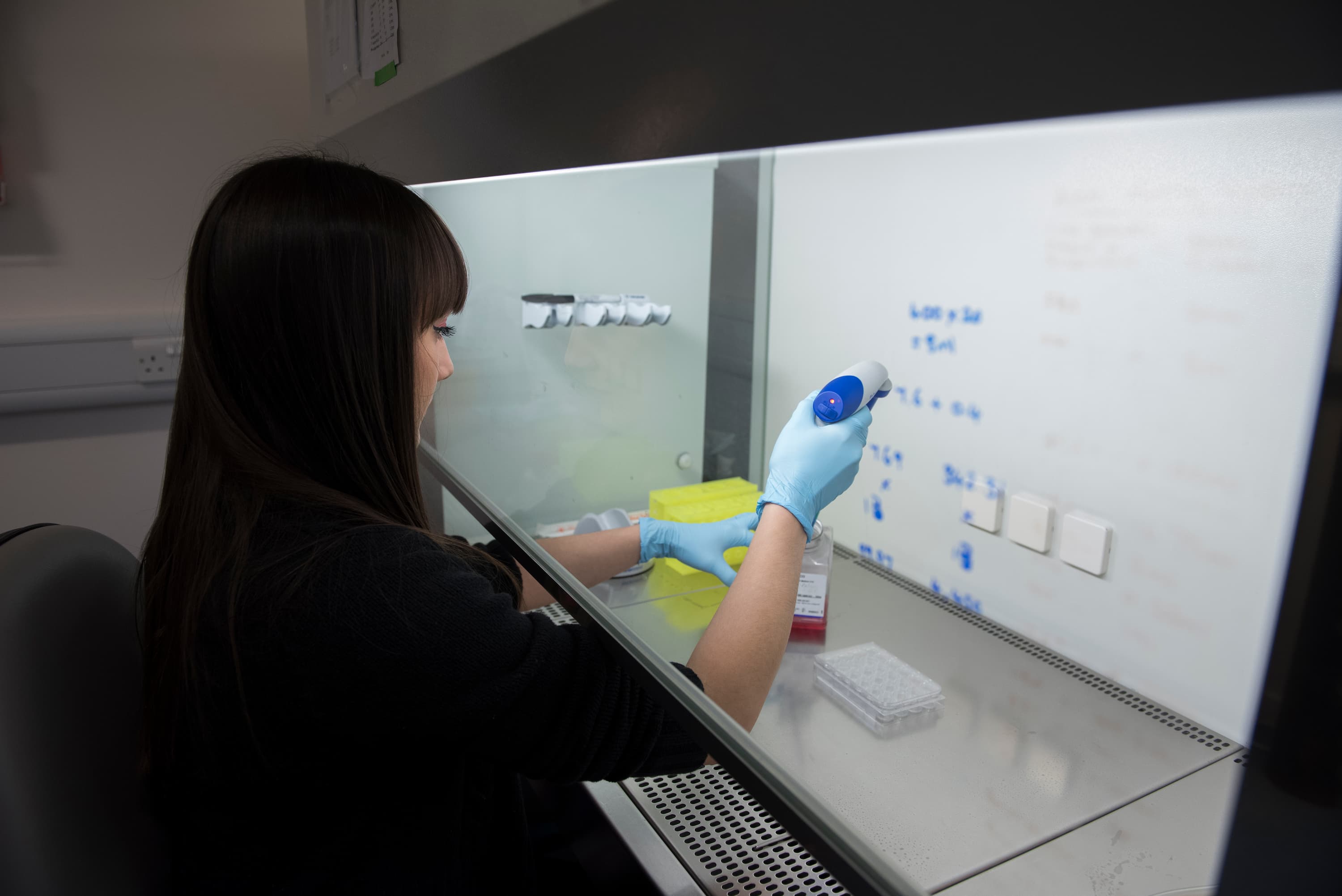

In this project, we’re looking at how these connections are changed by MND. We’ve been studying nanostructure – so at a really tiny scale – and were in the middle of a big tissue collection from different MND models when we shut down. It was frustrating, but it was out of our control.

Some of these samples had been aging for quite a while, and thankfully we managed to go into the lab on the odd day to collect tissue so it could be stored in the freezer. We were desperate to get back in and see what developments had occurred.

Missing my lab coat

Since I became Head of the University’s School of Psychology and Neuroscience, I don’t get to spend as much time in the lab as I used to, but I really value my hours in there. Having something that precious taken away completely, was hard to deal with.

But there was positives. We had more time to reflect, plan and think about our science – and we were able to talk together about our work a lot more.

It helped that the team were all set up with the technology to carry on working from home. And because we’re a small institution, we were able to be more flexible when it comes to collaboration and discussion.

There was also been a lot of writing going on. We analysed results and wrote up research findings, as well as worked on manuscripts, thought pieces and publications – all things that we'd normally struggle to find time to do.

One member of my team was midway through his PhD and managed to make good progress with his first chapter literature review, which is an essential part of his thesis. I kept reminding him how happy he would be when he came out with a finished chapter!

We also found new ways to stay connected. At the start of each week we held virtual lab meetings, and we all stayed up to date by evaluating the latest scientific literature in our regular journal clubs. And every Friday there was a virtual Q&A, where everyone had the chance to ask me what’s going on.

Heading back into the lab

But there’s only so much writing you can do and we were all quite ready to get back in the lab. We’d been discussing all along how to prepare ourselves for this part and we knew it would be gradual when we returned. We certainly didn't have a full lab at first. Instead we worked according to a timetable, with different members of the team going into the lab to conduct experiments at different times.

It’s a shame that timelines changed, and we were a little anxious about how much effort it would take to get going again. It’s hard to predict until you start trying. But we can say this for certain – we had done everything possible to ensure that we kept making progress in some way and that we used our time as constructively as possible.

Being pragmatic

Science is slow at the best of times, and quite stop-start. Sometimes things work, sometimes they don’t. This was a different kind of challenge, but ultimately not one that was going to hold us back. Over those months, we had time to reflect and prepare. And when we got into the lab again, your committed support ensured that we were ready to go. That’s why I’m so grateful to you for being a Cure Finder. Thank you.