A consultant based at the Francis Crick Institute, Professor Rickie Patani believes that stem cells could transform our understanding of MND. He’s using expertise to create better models of motor neurone disease.

“We’re making important strides forward in terms of our understanding at a molecular level what goes wrong in these cells and potentially how to target these processes,” he says. “It’s such an exciting time.”

Biography

I first studied neuroscience at medical school. It was complex, and our knowledge was limited, but the more I read, the more I looked down a microscope and looked at the structure of neurons and glia, the fantastic galaxy of cells…. I just found it mesmerising.

After graduating, I secured a higher training position in neurology, which came combined with a PhD at Cambridge University.

While I was there, I was really struck by the fact that we needed to understand how MND worked in humans. Animal models had been really valuable across basic and applied neuroscience. But they weren’t delivering the therapeutic advances we needed.

That’s why I decided to start working with human stem cells. I’ve never really looked back.

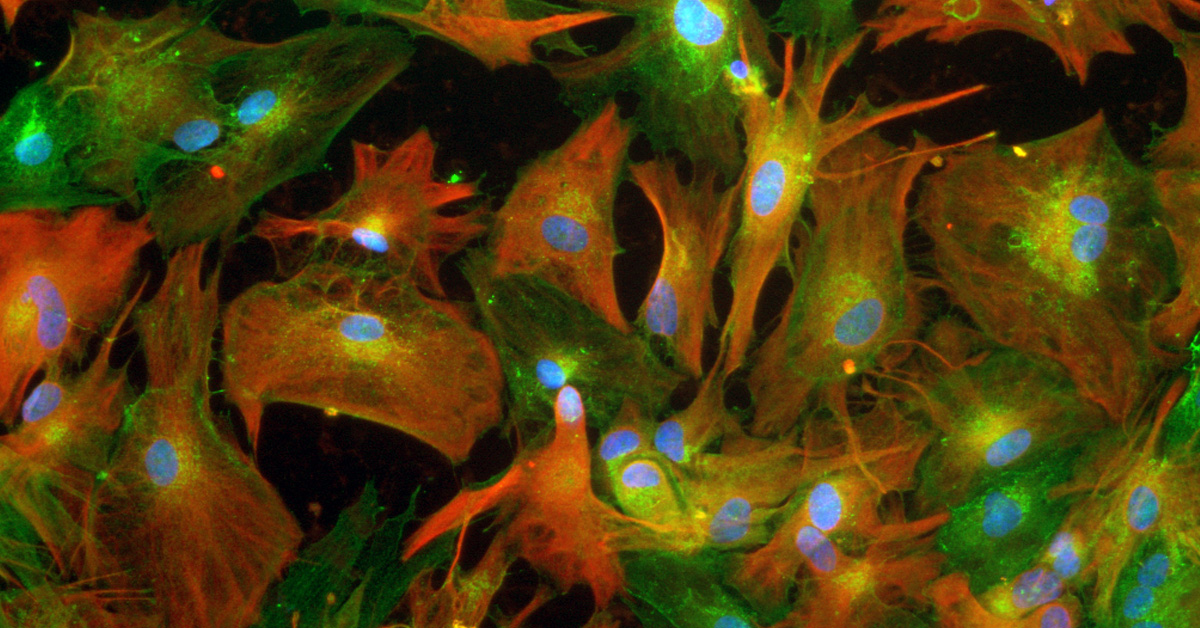

Professor Patani and his team have been investigated these star shaped cells called astrocytes which help motor neurones to function properly.

I started my lab at UCL in 2013 under the mentorship of a friend and collaborator, Jernej Ule. He’s a real pioneer in molecular biology – combined with the stem cell biology I’d been working on, I knew we’d have something powerful on our hands.

I became a consultant in 2017 and, have been seconded to the Francis Crick Institute from UCL since then.

At the end of 2018, I secured a Senior Clinical Fellowship, funded in partnership by the MND Association and Medical Research Council. That’s allowed me to expand my lab and really focus in on the molecular mechanisms that drive MND.

Now we’re working alongside researchers who study Alzheimer’s Disease and other forms of neurological disease, generating disease models by making region specific neurons and glia.

Life in the Lab

There are ten of us in the lab – an even split between post-docs and PhD students.

It’s a great place to work. People get on well with each other, they discuss science robustly, and support each other. I run the lab in a very specific way: we really operate on integrity above all else.

Professor Patani’s team at the Francis Crick Institute.

Together, we’re trying to understand the building blocks of MND. To do that, I believe we need to see how it works in real human bodies.

That’s where the stem cells come in: because, of course, they have the capacity to become any cell type in the body.

Now we’re transforming them into the cells which die when someone has MND, and support cells – specifically star-shaped cells called astrocytes.

The MND Association and MRC are funding my research into how three specific factors contribute to the motor nerve death in MND.

The first of these factors is the cell’s messaging service (called RNAs), which are made directly from the DNA blueprint. If you think of DNA as the cookbook, then RNA is a chef’s photocopy of the recipe, and proteins are what come out of the kitchen.

The second factor is establishing what role the astrocytes play in the process. The third is how ageing affects the disease.

Ageing is the biggest risk factor in MND but its relatively understudied. We want to understand directly how the mechanisms of ageing interface with the mechanisms of MND, and to address the question as to whether there is something that is potentially therapeutically targetable within the ageing process that’s been overlooked.

Professor Patani’s team working in the laboratory at the Francis Crick Institute, London.

Breaking down barriers

I’m also Ambassador of Clinical Medicine at the Crick, working closely with Nobel Prize-winner Sir Peter Ratcliffe. It really inspires me to see patients at the coal face, and bring these clinical insights back to the lab. We have launched a new scheme where we’re giving senior scientists the chance to sit in on clinics, and observe ward rounds.

It’s all about breaking down the barriers between medicine and science. That’s so important to me – I really believe that working together will get us to the breakthrough sooner.

Finding balance

I generally wake up between 4.30 and 5.15am out of habit really, but I do appreciate having a couple of solid (uninterrupted) hours to work each morning before heading in to the lab or hospital. The days are long and challenging, but it’s immensely rewarding work.

But now I have two children – a four-year-old daughter and a two-year-old son, and it’s made me want to strive for more balance. It’s certainly made me more time efficient.

What really made me happy recently was my son winning a prize in a school dancing competition. It made me so proud that it was the first prize he’d won, and that it was slightly out-there – it’s fantastic!

Dedicated to the cause

I’m utterly committed to MND. Why? Because it’s the most devastating disease I’ve ever come across.

I’ll never forget meeting my first patient with MND symptoms when I was starting out as a junior doctor. I remember thinking it was inconceivable we couldn’t do any more to help them. That sense of profound responsibility for patients has driven me ever since.

We’ve come a long way since then: for the first time we actually have the ability to look at what starts the disease process in different cell types. We’re making significant strides forward in terms of our understanding of what goes wrong in these cells at a molecular level and potentially how to target these processes.

There’s a group of really thoughtful MND researchers who are becoming more collaborative, interacting more. That’s helping us push things forward faster – it’s such an exciting time.